If pressure canning is essential, how have Germans been safely canning non-acidic foods for over a century without them?

- A personal curiosity that turned into a historical investigation

- In the beginning: a jar, a cookbook, and Aunt Sarah

- A smaller country, a shared knowledge base

- What did Rempel know?

- The role of scale and communication

- The USDA steps in

- A war effort, a canning crisis, and the turn to pressure

- Why pressure canning in Germany never caught on

- The rise of American regulatory hegemony

- Two ways of building trust

A personal curiosity that turned into a historical investigation

It started with a simple question: why is pressure canning in Germany practically nonexistent, while Americans treat it as the only safe way to preserve non-acidic foods? That curiosity pulled a thread that started unraveling a bigger story.

I didn’t just want to know what happened and when in canning history. I wanted to understand how two countries ended up with such different kitchen traditions – and what that says about trust, risk, and the way knowledge spreads. To figure that out, I had to step back from the timeline and look at the broader context. Who were the people doing this work? What kind of world were they living in? And what shaped their ideas about safety, trust, and technique?

In the beginning: a jar, a cookbook, and Aunt Sarah

Let’s start in the U.S., in 1858, with the invention of the Mason jar.(1) It was a major step forward in food preservation technology – but it didn’t spark an immediate revolution. Glass jars were still relatively expensive, and canning knowledge wasn’t widespread. Early American cookbooks – even those written by respected domestic educators – reveal a patchwork of methods and advice.

One cookbook I found, Mary at the Farm and Book of Recipes Compiled During Her Visit Among the “Pennsylvania Germans,” (2) had a recipe for canning green beans that started out reasonable. But after boiling and sealing the jars, the instructions called for reopening them, adding more water, and simply closing them again – all without further sterilization. No explanation as to why, but in a later recipe for Aunt Sarah’s Method for Canning Corn, it was noted that she’d “used this recipe for years and ‘twas seldom she lost a can.”

It’s a bit comical, but it’s also revealing. In early American home canning, there was no single protocol, no common safety baseline. People followed whatever their family – or some other trusted source – had done. And in many cases, that was the only option. There were no guidelines, no easy access to scientific information. If a method had worked before, it was reason enough to keep doing it.

A smaller country, a shared knowledge base

Meanwhile in Germany, things looked vastly different. The country was geographically smaller, and cookbooks like those by Henriette Davidis were widely read and respected. Davidis’s 1874 cookbook, Praktisches Kochbuch für gewöhnliche und feinere Küche (Practical Cookbook for Everyday and Fine Cuisine) (3), included remarkably detailed instructions for canning vegetables in tin cans: cleanliness, proper sealing, correct headspace, and heat were all emphasized. She underscored the importance of proper technique over and over. She treated canning as a methodical process.

That widespread consistency didn’t mean standardization – not in the regulatory sense. But it did mean a shared cultural understanding. So when Rudolf Rempel and his wife Maria began experimenting with glass jars and water bath sterilization in the 1890s (4), they weren’t introducing a foreign concept. They were simply refining a process people already understood and making it more accessible to people who didn’t have a nearby tinsmith to properly seal their cans.

What did Rempel know?

Did Rempel know about Mason jars? Did he ever see one? Was he aware that Aunt Sarah was boiling her green beans and topping them off with more water? Probably not. But it’s a curious thing to think about.

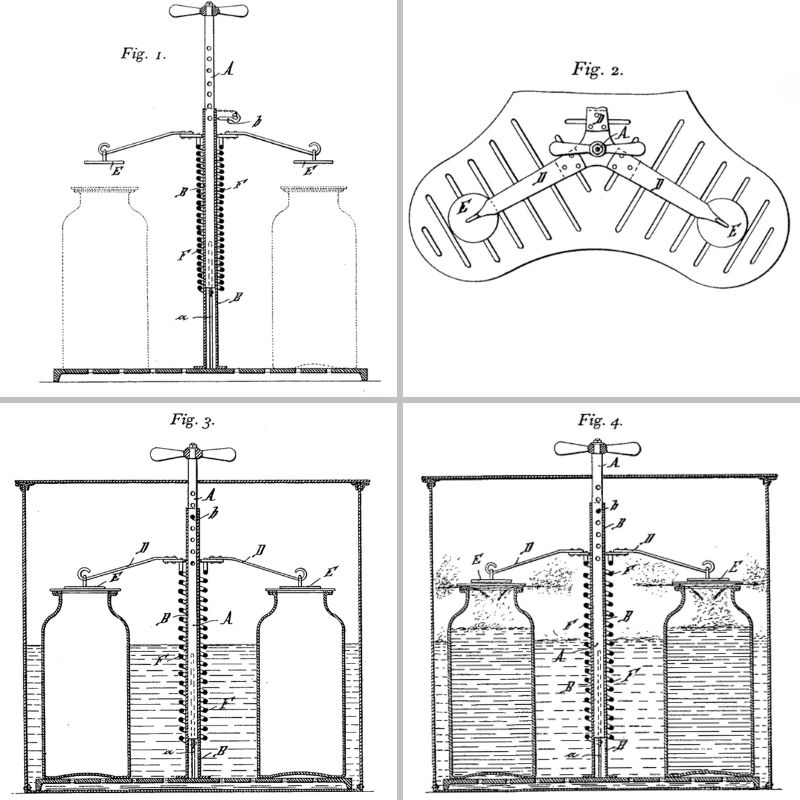

Rempel was a chemist by training, working in Germany’s industrial Ruhr Valley at the Gelsenkirchener Aktiengesellschaft für Kohledestillation (Gelsenkirchen Coal Distillation Company). He started his food sterilization experiments in the company lab: grinding down the rims of glass jars, sealing them with a rubber ring and a tin lid, then boiling them in a water bath with weights on top to hold the lids in place.

Encouraged by his early success, he and his wife Maria continued the experiments in their home kitchen. Using produce from their own garden, they dedicated their Sundays to refining the process together. They weren’t just testing a household trick. They were documenting, experimenting, improving. Maria helped polish the jar rims with sanding powder. They monitored how the food looked and tasted months later. They wanted the food they preserved to be not only safe – but also beautiful.

In 1892, Rempel filed a patent for his device: a jar with a rubber ring and a lid held under pressure during boiling. The patent, titled Vorrichtung zum Einkochen von Nahrungsmitteln in Gläsern (Device for Preserving Food in Jars) (5), allowed for air removal and vacuum sealing. The following year, he died at just 34. He didn’t live to see the success of his invention – but Johann Weck one day would.

The process Rempel and Weck helped refine would eventually become the backbone of German water bath canning – a method passed down not through law, but through habit and trust.

Cross-section of Rempel’s device in action during sterilization [1] Jars are submerged in a hot water bath [3], their lids gently held in place by pressure plates [2]. As the temperature rises, a spring mechanism responds, lifting slightly to let trapped air escape from inside the jars [4].

The role of scale and communication

Part of why the American home canning experience took a different path has to do with geography and communication. The U.S. was vast, and information spread unevenly. People learned canning from neighbors, family members, or local cookbooks. What Fannie Farmer recommended in her popular Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (6) wasn’t the same as what Mrs. Simon Kander suggested in The Way to a Man’s Heart – The Settlement Cook Book (7) from Wisconsin. And both differed from how Aunt Sarah was doing it in Pennsylvania (2). The result was wide variation, and with it, greater risk.

The USDA steps in

To understand how and why the United States Department of Agriculture got involved in mitigating this risk, it helps to go back to its roots. The USDA was founded in 1862 by President Abraham Lincoln as a research and support agency for American farmers. (8) Lincoln called it the “People’s Department” because at that time, half the U.S. population lived on farms. At first, the USDA focused on agricultural productivity – collecting seeds, studying soil, and promoting better farming practices. Food safety wasn’t part of its original mandate.

But they didn’t stay in the background for long. Rising public anxiety over contaminated food and appalling conditions in the meatpacking industry pushed the agency into a new role. Suddenly, they weren’t just helping farmers grow food; they were making sure that food was safe to eat. That shift eventually extended to home kitchens too, as the department began issuing preservation guidelines aimed at protecting families from invisible dangers like botulism. (8)

In 1909, the USDA published Farmer’s Bulletin 359, which explained the whys and hows of the science behind sterilization. (9) It recommended a process of fractional sterilization where jars of low-acid foods were boiled for an hour on three consecutive days. The method was based on sound microbiological principles aimed at eliminating spores that could cause spoilage or illness, but it was also time-consuming and labor-intensive.

Many home canners didn’t adopt it. Maybe they never saw the bulletin, maybe they trusted the methods they already knew, or maybe they just didn’t want to follow such a cumbersome process.

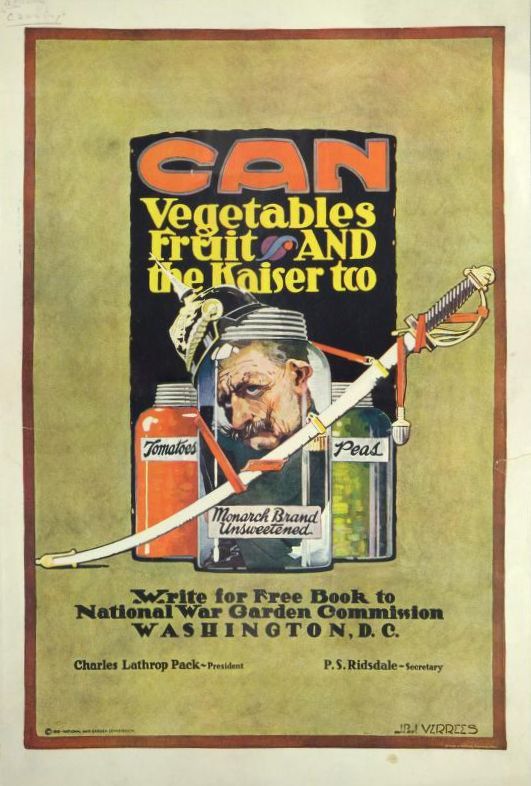

A war effort, a canning crisis, and the turn to pressure

Then in 1917, the U.S. joined World War I. With food shortages looming and the government urging Americans to grow and preserve their own food, home canning was poised to become a national priority. But there was a problem: if left to their own devices, millions of Americans would be canning at home using inconsistent, potentially dangerous methods. Spoilage and even cases of botulism would be likely. The USDA needed a single, reliable process to make food safe, even when the canner didn’t know exactly what they were doing.

The government launched large-scale education and outreach programs through the Cooperative Extension Service. The USDA declared pressure canning to be the only safe method for home canning, and home demonstration agents traveled across the country teaching people how to do it. Community canning centers offered shared equipment and trained guidance to help families preserve food safely and efficiently. (1)

During World War I, home canning became a patriotic duty in the United States. Posters like this encouraged families to preserve food as part of the war effort. Image credit: Courtesy of the National Agricultural Library, USDA. “Can Vegetables, Fruit and the Kaiser Too” (1918). Public domain.

Why pressure canning? As early as 1895, the commercial canning industry had begun turning to pressure sterilization for low-acid foods, thanks to research by Samuel Cate Prescott and William Lyman Underwood at MIT. (10) They were trying to solve a stubborn problem: even after boiling canned foods, some still spoiled. Their experiments showed that applying higher heat under pressure could effectively keep food shelf stable.

The USDA was building on commercial canning standards in promoting pressure canning. It wasn’t just about preventing rare but serious risks – it was about protecting public health. Pressure canning was more efficient, more reliable, and more likely to succeed even if a home canner deviated slightly from the instructions. Compared to the multiple water bath boilings the USDA had previously recommended, it also saved time, effort, and fuel.

From that point forward, USDA guidance became both scientific policy and public expectation. It offered clarity and protection but also marked the beginning of a one-size-fits-all model of food safety. With pressure canning now the gold standard, there was no reason to test or approve any other method.

Why pressure canning in Germany never caught on

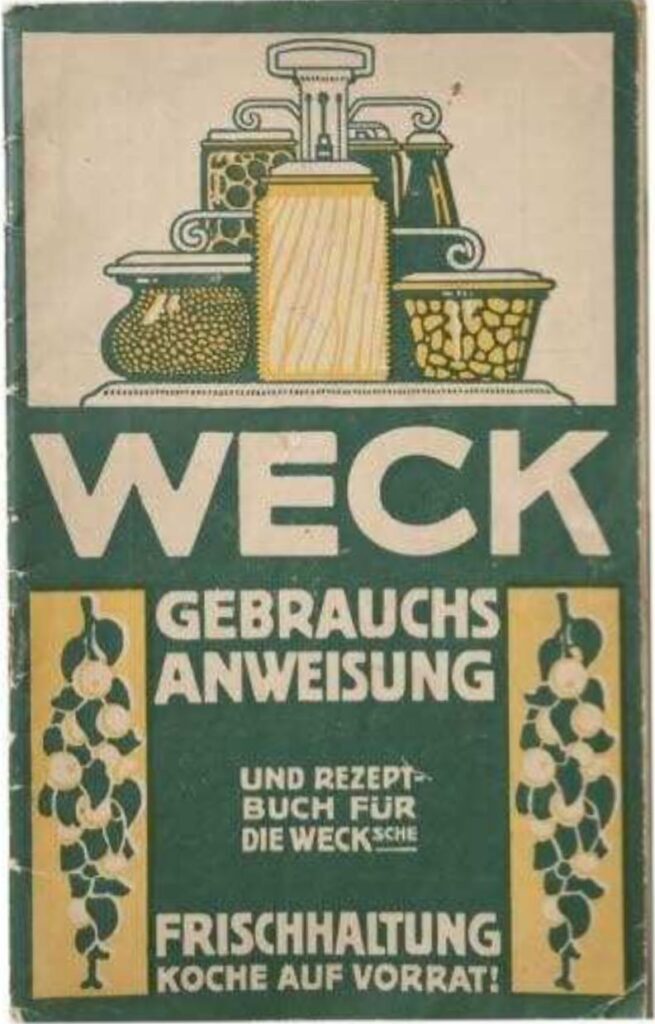

But while the U.S. system settled into a single sanctioned method, Germany’s path was evolving in a different, more decentralized way. German households continued to rely on consistent, familiar protocols. When the Weck company took over Rempel’s patent, they didn’t just manufacture jars – they built a system. Johann Carl Weck, a merchant and wellness enthusiast, partnered with J.W. van Eyck, an energetic businessman with a flair for marketing. (11,12) While Weck soon left the business, it was van Eyck who brought the vision to life.

Under his leadership, the company didn’t simply sell equipment. It sold education. Home economists and cooking teachers gave live demonstrations in schools, parish halls, and local clubs. Booklets and brochures laid out the method step by step. With standardized jars, reliable closures, and accessible instructions, the process became second nature.

Weck Instruction Booklet, circa 1915 (from the Werkbundarchiv – Museum of Things, Berlin)

It was a different kind of standardization – not top-down, but bottom-up. Not enforced by regulation, but spread through culture and shared practice. As a result, even without government mandates, the method became deeply trusted. People knew what to do and why they were doing it.

The rise of American regulatory hegemony

Over time, what started as helpful guidance became something more rigid. Many people continued using water bath canning, and guides from companies like Kerr (13) included detailed instructions well into the 1940s – methods that, interestingly, resemble those still used in Germany today. But in the U.S., they came with caveats: boil for hours, reheat before eating, use at your own risk.

Meanwhile, the pressure canning standard wasn’t just a reflection of safety. It was also about practicality. It accounted for scale, energy use, equipment availability, and the wide variability in home practices. A single standardized method, backed by government authority, was easier to teach, easier to trust, and harder to misuse. Eventually, those decisions became tradition – and tradition became expectation. That’s part of why many Americans use pressure canners without questioning the alternatives.

In a country where people had long relied on scattered advice and kitchen improvisation, a single, authoritative solution made sense. But in Germany – where clear, consistent techniques had been part of the cultural fabric for decades – a top-down mandate just wasn’t needed. That cultural consistency is part of why Germans don’t use pressure canners, even for foods considered risky in the U.S.

Two ways of building trust

Canning isn’t just about preserving food. It’s about preserving trust – in your method, your tools, your community, your knowledge. In the U.S., that trust was placed in institutions. The USDA became the arbiter of safety, providing a single, standardized path that anyone could follow. In Germany, trust came from a shared cultural understanding: methodical, consistent, and reinforced by education rather than regulation.

Neither model is inherently better – they just work in different ways. Recognizing that can help us move beyond the idea that there’s only one safe method. Safety doesn’t come from dogma. It comes from knowing what you’re doing, why it works, and how to do it right.

But even in Germany, the story is shifting.

The Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) was established in 2002 after the “mad cow disease” crisis, tasked with providing independent, science-based guidance on consumer health and food safety. While it has no regulatory power, its statements carry influence. And in recent years, some of its canning advice has begun to echo USDA-style messaging – framing pressure canning as essential and stating, for example, that Clostridium botulinum spores “can only be inactivated at temperatures above 100 °C.” (14)

That claim oversimplifies what the science actually shows – something I explore more fully in another post about what “safe” really means.

Despite the BfR recommendations, most German home canners continue to can as they always have – relying on careful tradition, clean technique, and the quiet confidence of a method that’s worked for generations. That tradition is the foundation of German water bath canning. In my next post, I break down seven features that make the German method work.

Maybe Aunt Sarah, with her vaguely described green bean recipe, just had a lot of luck on her side. But her story, like Maria Rempel’s, is part of a larger moment in food history – one shaped by trial, error, tradition, and science. And while one path led to centralized rules and another to decentralized skill, both began with the same question: how do I make this food last, while keeping the people I love safe?

References

- How did we can? The evolution of home canning practices. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://www.nal.usda.gov/exhibits/ipd/canning/timeline-table

- Thomas E. Mary at the Farm and Book of Recipes: Compiled during Her Visit among the “Pennsylvania Germans.” John Hartenstine; 1915. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://d.lib.msu.edu/fa/52

- Davidis H. Praktisches Kochbuch Für Gewöhnliche Und Feinere Küche. Velhagen & Klasing; 1874. https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/details/bsb11188024

- Ehepaar Maria D, Rempel hatte R. Maria und Rudolf Rempel Die Entdeckung des “Einweckens.” 2025. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://www.gelsenkirchen.de/de/stadtprofil/stadtgeschichten/gelsenkirchener_persoenlichkeiten/maria_und_rudolf_rempel.aspx

- Rempel R. Apparat zum selbstthätigen Schließen und Entlüften von Sterilisirgefäßen. Published online April 24, 1892. https://depatisnet.dpma.de/DepatisNet/depatisnet?action=pdf&docid=DE000000066898A&xxxfull=1

- Farmer F. The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book. Little, Brown, and Company; 1896. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://n2t.net/ark:/85335/m5fn15277

- Kander SM. The Settlement Cook Book: Containing Many Recipes Used in Settlement Cooking Classes, the Milwaukee Public School Cooking Centers and Gathered from Various Other Reliable Sources. J.H. Yewdale & Sons Co. Printers; 1901. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://n2t.net/ark:/85335/m51z45z1h

- Development of Canning in the US. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://www.meatsandsausages.com/canning/food/history-usa

- Breazeale JF. Farmer’s Bulletin 359. Canning Vegetables in the Home.; 1909. https://archive.org/details/sim_farmers-bulletin_1910_359

- Prescott SC, Underwood WL. Contributions to Our Knowledge of Micro-Organisms and Sterilizing Processes in the Canning Industries. Science (1979). 1897;6(152):800-802. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6.152.800

- Weck Glass and Packaging GmbH. Die Geschichte Der Firma WECK.; 2019. https://www.weck.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Geschichte_WECK.pdf

- Einkochwelt. Erfindung des Einkochens. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://www.einkochwelt.de/wissenswertes/erfindung-des-einkochens.html

- Home Canning Guide by Kerr. Bulletin No. 841. Kerr Glass Manufacturing Corporation; 1941.

- German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment. Rare but Avoidable: Questions and Answers about Botulism – Updated BfR FAQ. 2023. Accessed May 25, 2025. https://www.bfr.bund.de/en/service/frequently-asked-questions/topic/rare-but-avoidable-questions-and-answers-about-botulism/

Julie is a biologist turned science writer living in Germany. She shares her passion for traditional German water bath canning, seasonal cooking, and gardening on Old World Preserves.